After a dreadful week in London full of grey, relentless skies, the sun finally shone on Valentine’s Day. A miracle had taken place, and it was time to make the most of it. My first solo-date of the week would be to see the much talked about Noah Davis exhibition at the Barbican. The show had been on my ‘to do’ list for several weeks, but when a dear friend who lives in New York mentioned coming across his work, and linked me to his show in London, I took it as a sign to go. I’m glad I did, because it touched me (and still touches me) profoundly.

The last time I was swept away by an exhibition was at the Tate Modern in 2015 for Marlene Dumas retrospective ‘The Image as Burden’. (Oddly, 2015 is the year that Davis died.) I was so enamoured I came away from the show with an armful of memorabilia—the exhibition book, a book of her poetry and prose, and a postcard which I have on my wall to this day. I can still see myself standing in that gift shop, manic and overwhelmed, approaching the till with all my stuff, and running into a woman saddled with the same objects. We caught each other's eyes and laughed, the two of us drunk on the work we’d seen. Two fan girls with a similar temperament. It’s a day I’ll never forget. Just like that day at the Tate, I left the Noah Davis show with similar items—a testament to the power of the exhibition. If there’s one thing I love other than seeing an impactful show, it’s treating myself to little gifts that I might remember for years to come.

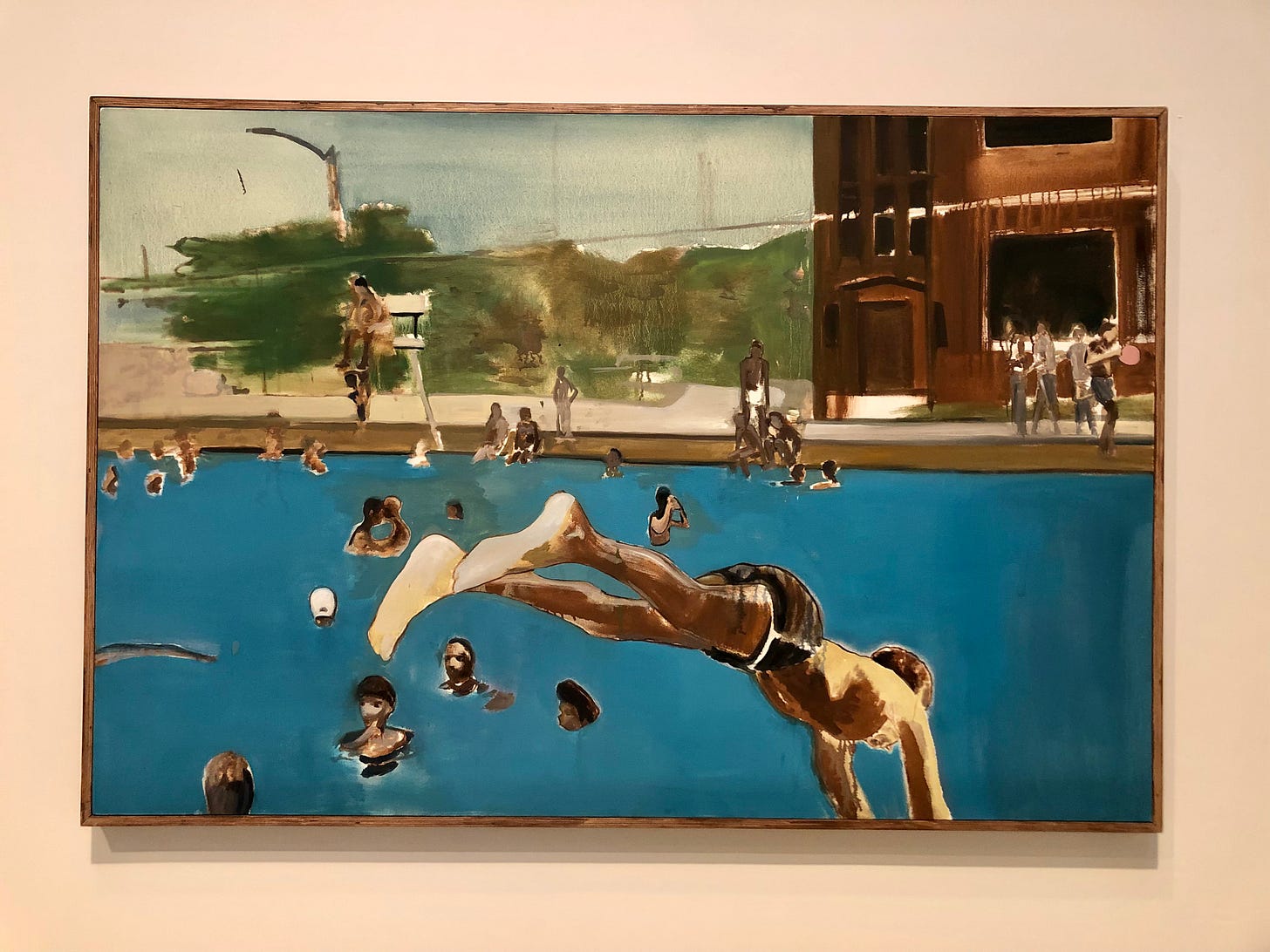

I came away from Davis’s paintings feeling touched and raw. I would’ve ugly cried if I could’ve, but there were too many people in the gallery, and the English aren’t really the type for public emotions. At various points in the afternoon, my lips literally quivered as tears stung my eyes. It wasn’t just the ceaseless devotion to his work that moved me, it was his skill, and the ethereal way he rendered day to day black life in Los Angeles. Davis’s paintings were inspired by photographs of random strangers found in flea markets, which he translated into his own worldview, or stills from trashy American television shows, or scenes of children swimming and having a good time in urban pools. When life sometimes feels mundane or routine, or even ugly and cruel, Davis strove to inject the fantastical and the magical into it all. I took myself out to see the show in part because I wanted that experience of elevation, even if for a couple of hours. The sun had finally come out, but I still needed that extra bit of inspiration and aliveness in my day. I tend to have high expectations when I visit museums or galleries, often leaving disappointed. At best, I want to be touched and transported, a high order and rare occurrence, but Davis’s work delivered. To be honest, I’m still emotional several hours on, reminding me of a quote by Audre Lorde I came across this week from her essay, ‘Uses of the Erotic’ (which you should read or reread). In it she says, “The need for sharing deep feeling is a human need.” I crave this type of feeling often, even though I’ve come to understand it’s not for everyone, and not everyone is capable of it. In an increasingly divisive, dissociated and desensitised world, we need feeling more than ever.

Davis’s work struck parts of me that are naturally sensitive and empathic, but I’ll caveat to say that I’m also extremely premenstrual! What struck me most was the spectre of Davis’s early death amidst his beautiful and prolific output. I couldn’t help but think what I always think when I take in a show: what is this obsession, this need to create? So many artists have this natural compulsion; I’ve been to countless exhibitions of well-known and lesser-known artists who have clearly expressed it in the breadth of their work, but with Davis’s, I couldn’t help but be reminded that everything here and more he made by the age of 32, when he died of a rare type of cancer. He painted until the very end. I couldn’t believe that I’d never heard of Davis before, but I felt honoured to be witnessing his life and work that day. It’s a theme that seems to be following me around, actually—this idea of creation, legacy and being remembered. I spent the last couple of years co-writing a biography on a forgotten and cast aside figure in history, the poet, playwright, activist and journalist Una Marson, a creative powerhouse born and bred in Jamaica, who lived in London for many years and became the first black female radio presenter at the BBC. Unlike Davis, Marson passed away without a strong sense of belonging or community, and as I walked amongst his paintings, the show had me thinking about what it means to create community, whether in-person (as Davis and his wife Karon did through co-founding the Underground Museum in 2012, a project that began by renting out storefronts in Arlington Heights, Los Angeles, a neighbourhood not typically known at the time for culture of that kind), or through the visual representation of a larger human community as Davis documents in his work. We need more people creating out of the box, creating just for the hell of it, creating to bring people together, conceiving of their own worldviews beyond the mediocrity that’s peddled to us.

Many of Davis’s paintings arrested me, but it was ‘Painting for My Dad’ that broke me. He painted this while his father, Keven, was dying from terminal cancer in 2011, and Davis himself would be diagnosed about two years after his father died. I stopped and stood and stared for a long time and couldn’t help but feel as if I’d fallen into an abyss, my favourite feeling. A lone man (Davis’s father) stands inside the mouth of an opening, boulders either side of him, his back to the viewer. A night sky full of stars is just before him. He stands on the edge of a cliff, a lantern in his left hand. His shoulders are hunched, his body leans forward with curiosity and fear. It feels like he’s checking out what’s in store, perhaps even remembering from where he came, and from where he’ll soon return. I could feel Davis contemplating his father’s impending death, wondering about the journey he’d soon embark on from this life to the next. I was reminded, once again, of the fundamental truth of our existence as I stared at the fragility of that figure against the vastness of the landscape, looking out into the unknown, dressed in a simple red t-shirt and jeans.

Even beyond death, Davis’s spirit permeated the enormous gallery. It was as if the curators too had helped to bring his essence back to life. Those who know me, know that I’ve been exploring the world of the psychic or intuitive arts over the last couple of years, so ideas of interconnectedness, vibration, and energy have been at the forefront of my mind. It occurred to me that painting and what an artist leaves behind is another form of spirit communication, and it’s this limitlessness of our souls, and in Davis’s work, that I find so appealing. Perhaps an obsession or a compulsion to create stems from a primordial place, a deep understanding of our true natures as reflected to us by nature and by the ultimate creator itself.

I really enjoyed reading this Jennifer, in particular about finding a place in that community. Also it’s made me question my appreciation of creation in galleries, I dont think I appreciate it enough to be honest, at least not to the extent how Davis’s work made you feel. Your essay has made me want to visit more galleries and learn more about creations. Thank you for sharing this xx